"7 Weizmann St.", D&A Contemporary Photography Group Gallery, Tel-Aviv

"Unlike the fine art objects of pre-democratic eras, photographs don't seem deeply beholden to the intentions of an artist. Rather, they owe their existence to a loose cooperation (quasi-magical, quasi-accidental) between photographer and subject mediated by an ever simpler and more automated machine, which is tireless, and which, even when capricious, can produce a result that is interesting and never entirely wrong... In the fairy-tale of photography the magic box insures veracity and banishes error, compensates for inexperience and rewards innocence."

Although these words were written in the 1970s, it seems their relevance has not been lost in the shift to digital

and cellular [phone] photography.

It appears that photography, as a medium, has become both fundamental and available to all. Digital

photography is more prolific than any other, and is at everyone’s fingertips through cell-phone cameras.

Photography has become a basic and common means of communication, convenient and readily available.

Photographic messages are sent frequently (just like text messages) via cell-phones, so that the image-message

is experiential and testimonial, as if to say: 'I'm here' or 'Look at this'.

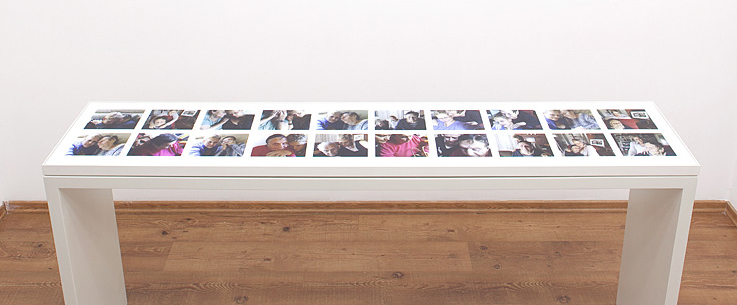

Central to Yudith Schreiber's '7 Weitzmann st.' are digital photographs taken on her mobile phone. Schreiber

photographs herself and her parents while on visits to their home.

"I photograph myself in my parents presence. Portraying beauty doesn't matter to me; I am devoted instead

to the encounter, to the embrace, the touch, the closeness, and through this I photograph. I photograph in

order to see. I photograph in order to feel."

Schreiber doesn't see while she is photographing. She reaches a long arm out beyond the embrace and

takes a shot. The ease with which the image is taken and burned onto the memory card is at odds with the

photographic result, which reveals the passage of time and the mental and emotional complexity inherent to

the images. Yudith Schreiber is a daughter, and mother and a grandmother. Through photography she asks

to stop time and examine her own presence within this familial tapestry. When she photographs, she gazes

at the past, present and future.

"Nobody ever discovered ugliness through photographs. But many, through photographs, have discovered beauty. Except for those situations in which the camera is used to document, or to mark social rites, what moves people to take photographs is finding something beautiful. (The name under which Fox Talbot patented the photograph in 1842 was the calotype: from kalos, beautiful.) ...So successful has been the camera's role in beautifying the world that photographs, rather than the world, have become the standard of the beautiful... The history of photography could be recapitulated as the struggle between two different imperatives: beautification, which comes from the fine arts, and truth-telling, which is measured not only by a notion of value-free truth, a legacy from the sciences, but by a moralized ideal of truth-telling, adapted from 19th century literary models and from the (then) new profession of independent journalism."

‘It's important for me to say that I photograph myself, that my work is about me, 'Schreiber notes when

looking at her images, and so, while performing an effortless and incidental photographic routine during her

regular and scheduled visits, Schreiber examines her relationships within the family unit; her relationship with

her parents in general, to her mother specifically, and to her daughters.

She gauges her own image, that grows and grows through the photographs, as it is reflected in her photographed

parents. She evaluates the resemblance between them as it spreads over time and sees through it the potential

of morals and ethics being passed on to her daughters.

The photographs carry an extremely personal weight, as if they would 'normally' have remained in the family

album, or not even venture out of the mobile phone. Schreiber, however, opts to confront the photographic

result, to connect to her resemblance to her parents' image, to accept the visible passage of time and age and

to examine the boundaries of intimacy through 'artistic means'.

Thus, the cellular snapshot becomes an object, sculptural furniture that holds the genetic code of emotions and

sensations. Schreiber's personal album – like a vitrine enables a peek into the private, honest space in which

the photographs are carriers of a genetic truth.

This type of photography might appear as a preoccupation with loss; the document as that which represents,

or even creates, the past, the passing moment.

Alongside the smiles peering out of the frames, there is a general sense of melancholy, and the photographs

relay the content of what has been. However, their presentation (as object or furniture, shiny or matte) enables

a process of disengagement from the melancholic dimension, and a convergence into the piece itself.

In her book, Black Sun: Depression and Melanholia, Julia Kristeva addresses beauty as the other world of the

depressive. She describes the following process of alienation:

"When we have been able to go through our melancholia, to the point of becoming interested in the life of

signs, beauty may also grab hold of us to bear witness for someone who grandly discovered the royal way

through which humanity transcends the grief of being apart: the way of speech given to suffering, including

screams, music, silence, and laughter."

And in Schreiber's case, photography.

David Adika curator